The Problem with “AI Scales”, and What Teachers can Use Instead

Summary

AI scales, meant to clarify appropriate AI use in assessments, can be useful - but also problematic.

Scales such as the one analyzed here focus on authorship rather than on learning, but the two are distinct

Instead of AI Scales, teachers can use a simple but powerful Golden Rule

AI Scales: Useful and Problematic

Concerns around student misuse of Generative AI have led to the development of AI scales, a concept originally developed (to my knowledge) by Leon Furze.

While these scales can be useful (I developed one myself based on a friendly critique of Leon Furze’s initial AIAS), and are always a better option than a blanket ban on GenAI tools (which deprives students of their benefits and fails to prepare them for the future), they can also be problematic.

A good illustration of these problems is the “Classroom AI Use” graph below, which proposes 12 steps, from “Student does all the work…” to “AI does student work for them…”.

Note. This critique of Matt Miller’s work is also intended to be a friendly one. EduAI integration is a new and developing field, so it is to be expected that we continuously improve our models are we reflect on them.

Assessing Products v. Assessing Learning Objectives

Asking “What’s cheating? What’s ok?”, this scale assumes that the point of an assessment is for students to do a certain type of work and to submit a certain type of product (e.g., an essay). While this might seem obvious, it is actually not true: the point of an assessment should be for students to demonstrate targeted learning objectives, and thus to perform certain cognitive operations (such as “critically evaluating a source for limitations”, for instance).

Next, this scale also assumes that such products (essay, book report) are graded for their overall quality, rather than with precise, standards-based rubrics. If I assign “an essay” and grade it as a “90%” or an “A” , then I need to know who is the real author of this product: the student, or AI. However, if I assess targeted understandings and skills, then the important question is not “who wrote this?”, but “who performed these specific cognitive operations?”

To see how these two questions differ, let’s look at the scale again. Imagine that I assigned a book report to assess students’ understanding of a novel and ability to explore multiple interpretations critically. Why is the descriptor “Student writes all content but asks AI for feedback to improve” so low? Here, the student may be doing the bulk of the writing, but the specific skills I am looking for might actually come from the AI feedback. The issue is that the scale tries to assess who did the “heavy work” in creating the product, when it should focus on who did the “fine work” of demonstrating mastery of the learning objectives.

Similarly, why is the descriptor “AI writes content but student edits based on learning from class” so high? Here, the student may not be doing the busy, initial work of stringing words together, but they might be the one doing the relevant cognitive lift by assessing, correcting, and adding to the AI work to achieve the learning outcomes.

This example tells us a number of things.

First, that there is a difference between the proportion of work done and the authenticity of the learning displayed. Students might do almost all of the writing, but have the AI perform the cognitive operations being assessed. Conversely, they might demonstrate the latter, and leverage AI to do everything else.

Second, that AI scales should not be used to gauge how much AI was used overall in the creation of a product, but how much it was used at the specific steps that are being assessed. AI scales largely replicate the production process of traditional assessments, such as essays:

[No AI]

Initial ideas/research

Outline

Draft

Feedback

Final product

[Full AI]If AI is only used to conduct research, the final paper itself might be safely attributable to the student, but this is irrelevant if the point was to assess their ability to do research.

As a matter of fact, the question is not how much they used AI for whatever purpose, but how well they used it for this specific purpose (with the understanding that the best and most appropriate use is sometimes: not at all).

What we need is thus not an AI Scale with fixed overall levels, but rather an AI Dashboard, with fine controls over AI use for different aspects of an assessment.

The Golden Rule of AI Use

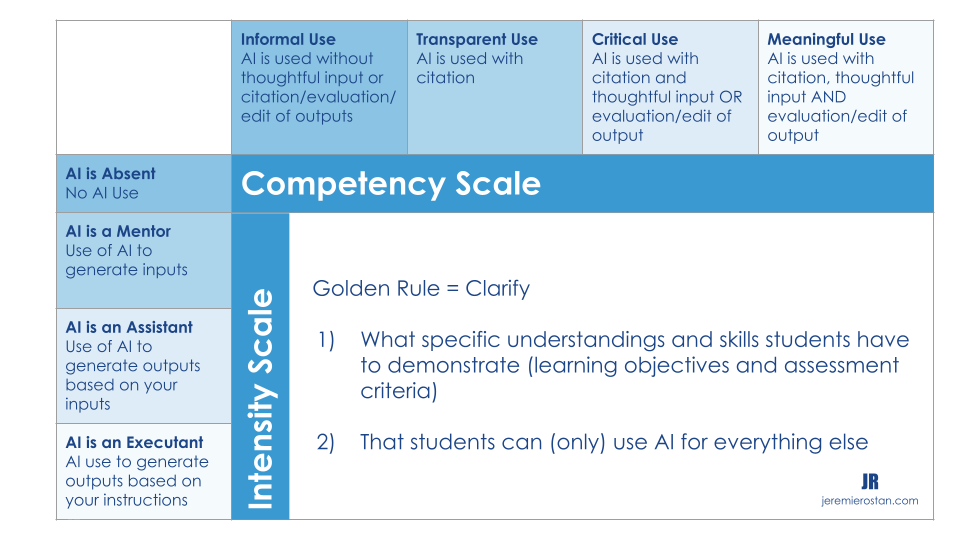

This is why the matrix I proposed in late 2023 was not organized by levels, but rather by categories applicable to each level.

Thus, AI can be used with meaningful student input (or not) at the brainstorming as well as at the editing stage — for instance with a carefully crafted prompt. Likewise, its outputs can be scrutinized and made one’s own (or not) at any step in the process.

Interestingly, this matrix already featured a “Golden Rule”:

“Students can use AI for everything — except for the specific cognitive operations that are being assessed.”

It is a good rule of thumb, but could be further improved. Undoubtedly, there are certain competencies that are important for students to develop, even if they will be able to delegate them to AI in the future, because they are fundamental:

They are part of what it means to be human

They are needed for people to be able to use AI effectively (very much like being able to calculate, and even more so being able to think mathematically, is necessary to be able to use a calculator effectively)

They are needed for people to be able to use AI responsibly, including evaluating its outputs and avoiding overreliance and dependence.

That being said, even the development, demonstration, and maintenance of these competencies can involve some AI assistance — as long as it facilitates their acquisition and is responsible.

Thus, all we need is arguably this Golden Rule:

“Students can use AI for everything — as long as they use it appropriately (effectively and responsibly) for this purpose, including demonstrating their own ability to achieve the learning objectives”.

A Shift and a Question

AI Scales usually describe how students are allowed to use AI to complete a particular assessment — thus assuming that they should not be using it by default or in other ways. In this regard, the Golden Rule operates a major shift by flipping the assumption and accepting that students use AI as needed, as long as it helps and does not hinder their learning (including by bypassing it).

The question, which is not answered by AI Scales either, then becomes: how can we know whether that is the case? This will be the topic of the last article in this series.

AI Scale Assurance:

Students can use AI for anything—as long as they use it appropriately (effectively and responsibly) for this purpose, including demonstrating their ability to achieve the learning objectives.